What is a tool?

Defining tool use

Humans are born tool users. I don’t just mean the high-tech screen you’re currently reading—we even use objects for such basics of life as walking, eating and protection. Other animals generally don’t do this, which over the centuries has been seized upon by those who like to speculate on what makes humans special. But if you want to claim that only humans do something, you really need to define exactly what that something is.

In this post, we will delve into the world of definitions, in an attempt to bring clarity—or at least explore the limits of debate—around just what tool use is. That question is far from settled, and to make sure we don’t miss anything we’ll be starting from scratch, as it were (scratching behaviour is a fine example of tool use, shared by elephants, some birds and many primates).

While the debate may be unresolved, that doesn’t make it worthless. When Plato defined humans as ‘featherless bipeds’ and Diogenes of Sinope responded by plucking a chicken and presenting it as a man, it didn’t discourage the Athenians from asking what people were. Instead, it prompted a search for more specific details (in the end Plato and his allies added ‘must have flat nails’ to their definition).

Definitions force us to be precise, and help us agree on the thing we’re examining. In an age where common ground is shrinking faster than Arctic ice, agreement is no small thing to aim for.

Leading by example

Definitions appeal to a certain mindset, especially the kind that can single-handedly write a complete Dictionary of the English Language, as Samuel Johnson did in the mid-eighteenth century. Johnson’s biographer, James Boswell, recorded the following conversation between the two of them in April 1778:

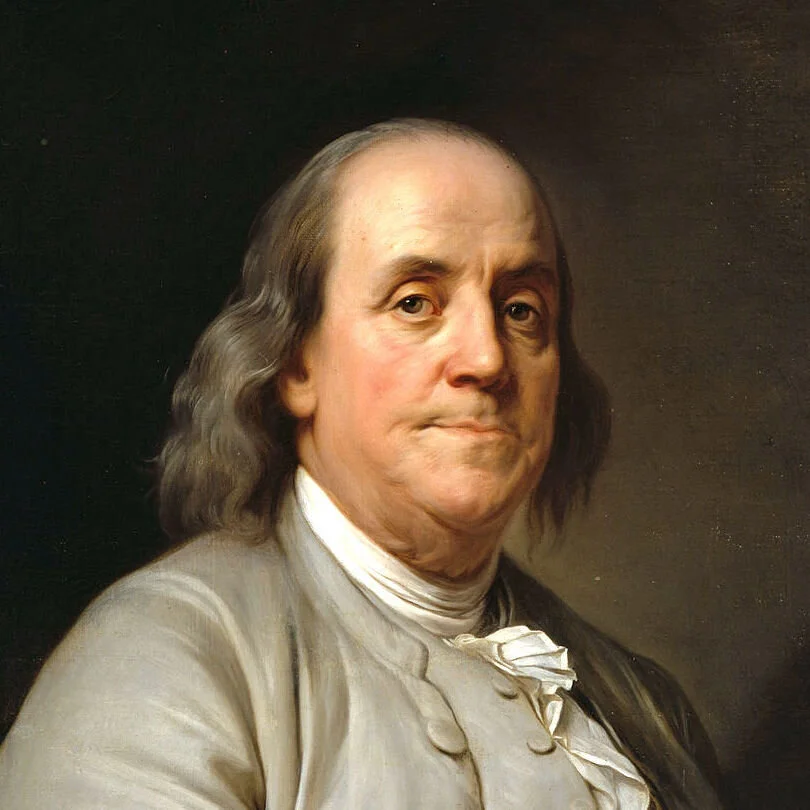

BOSWELL: ‘I think Dr. Franklin’s definition of Man a good one—‘A tool-making animal’. JOHNSON: ‘But many a man has never made a tool: and suppose a man without arms, he could not make a tool’.

The Franklin referred to was American inventor and statesman Benjamin Franklin, another devotee of precise language. The above lines are often recalled, but less quoted is the conversation that led up to it. Boswell and Johnson were discussing the value of definitions, and Johnson suggests that they are only useful up to the point where they become restrictive. His example is that everyone knows what a cow is, and adding extra details about its horns or digestive system might muddy the point, stating:

sometimes things may be made darker by a definition.

This advice is sound. Similarly, defining tool-use as ‘something only humans do’, which is essentially Franklin’s approach, precludes any further discussion and is therefore a step backwards in understanding the topic. (And trying to talk about ‘cow tools’ is only a recipe for confusion, as cartoonist Gary Larson discovered in the 1980s.)

To find the right level, then, let’s place you in the role of Franklin, or Plato. We can then apply the logic that ethologists have developed over the past few decades when narrowing down a definition of animal technology.

So, which of the following examples do you think involve tool use?

Scraping mud off the bottom of your shoe on a concrete path.

Splashing away a wasp that has landed beside you in a swimming pool.

Scratching an itch inside your ear with your fingernail.

Lifting up your young child to help you reach something from the top shelf in a supermarket.

Using chopsticks to eat noodles in a Japanese restaurant.

Adding a brick to the garden wall that you’re building.

Bringing bread home to your mother after she texted you asking to pick it up for her.

Take your time, and see if your responses have any common themes or objections. All done? Ok, let’s go through them one at a time.

Scenario 1 involves you scraping against part of the world. But importantly, you don’t have control over the concrete, or manipulate it in any way. That control is a key part of tool-use, which rules this example out. The reasoning is practical: inclusion would leave the definition far too wide to be of any value. opening it up to everything from bears scratching against trees to a hippopotamus cooling itself in mud. We don’t want to be too specific, heeding Johnson’s advice, but we do have to draw lines somewhere.

Scenario 2 (splashing the wasp) is more promising. The whole pool-full of water isn’t under your control, but those splashed waves wouldn’t be there without you, and they have the effect of keeping the wasp at bay. Your intention or purpose matters here, and it brings us to a second marker of tool use, which is that it should have a predictable effect on the world around you. In this light, your panicked splashing is definitely tool use, and you can happily join other water-tool-using animals such as archerfish and snapping shrimp.

What about Scenario 3? There’s definitely a goal in mind—calming your itchy ear—and you’re in charge of the finger. So it’s a tool, yes? Sadly, again no. Put simply, parts of your own body fall outside established definitions of tools. Reflection shows that this distinction is also necessary for the sake of sanity: without it every movement of every animal might be tool use. (Note that there could be an exception here for bodily secretions afterwards employed as a tool. We’ll look at an example of this at the end of the post.)

Scenario 4, in the supermarket, actually turns out to be quite straightforward. Your child is under your control and helps you achieve your goal—this is tool-use in action. The fact that they are a living being is irrelevant here (as is their level of understanding): they are a tool. However, if your child instead wraps herself around your leg and won’t let go, while you do the shopping, this does not automatically mean that the child is using you as a food-gathering tool. Control and purpose matter.

We actually have two ideas to consider in Scenario 5. First up: yes, chopsticks are tools. They are in fact one of the few remaining human examples of a relatively simple stick tool, along with walking sticks, baseball bats, toothpicks and pool cues. This kind of twig technology is more prevalent among other animals, including capuchin monkeys in Brazil that rouse lizards from stony cracks, finches in a Galapagos Island cloud forest that use cactus spines to pry out spiders from holes, and even alligators that sit patiently with sticks on their snout, waiting for a nesting bird to get a little bit too close.

The second concept in Scenario 5 is another boundary-defining one. Eating noodles, or any food, involves objects that we manipulate to achieve a goal (removing hunger). But it is far too common across species for it to help us understand tool use. The boundary set by ethologists is between things happening inside versus outside the body: only things happening externally count, even if we are deliberately causing interesting things to happen internally (when we take antibiotics, for example, or when a wild chimpanzee deliberately swallows whole leaves to clear out intestinal worms).

At first glance, Scenario 6 also seems to be clear cut example of tool use. You control the brick, your intention is to build a wall, job done. Right? Well… Here we confront the blurry line separating constructions from tools. Animal constructions, as thoroughly investigated by Mike Hansell (Emeritus Professor of Animal Architecture at the University of Glasgow), include things like bird nests, mole burrows, termite mounds and beaver dams. All those things require manipulation and an end-goal, but constructions are typically larger, more complex (meaning they have more parts), and are longer-lasting than animal tools. They are also more difficult to study, which shouldn’t really matter but does.

The division between tools and constructions deserves more attention, and much of human activity can be considered more construction-like than tool-like. It’s even possible that tool-use could be thought of as just one type of construction behaviour, which is often overlooked by researchers comparing other animals to humans. However, that discussion will need to wait for another post. For now, nests, mounds, dams and their like sit outside traditional definitions of tool use. Whether or not you agree with this perspective, Hansell summed his own opinion up fairly succinctly:

Those who feel that tools are ‘special’ might be correct – but they might be more special to researchers than to the animals that use them.

An informative addition

Finally, we reach Scenario 7. Texting may be a recent form of human long-distance communication, but animals such as whales and elephants have been sending messages across tens or hundreds of kilometres for a very long time. The notion that someone or something could be manipulated remotely, therefore, isn’t entirely new. But is this particular scenario tool use?

My own opinion is a tentative maybe, and here’s why. It’s easy for us to think of calls between animals, or mobile phone signals, as essentially having no direct link between the sender and receiver. But that’s not entirely true. Calls (animal) are physical vibrations in air or water, while calls (phone) manipulate an electromagnetic wave—both are invisible, but not intangible. This manipulation is purposeful and controlled, just like any tool use, and if someone texts you and you bring them a loaf of bread (as they intended) then their goal is successful.

I’m not suggesting that simply calling out to someone, whether person-to-person or between whales, or cicadas, or lions, is tool use. That would again leave the definition hollow. It is an open question, though, whether having the recipient of your message bring you something that you asked for makes them a tool. Perhaps they are part of a composite tool, along with the phone and communications system. If so, we are back again to constructions and their messy borders.

The notion of data transfer as part of tool use is not universally accepted, but it has gained some traction over the years. Computer scientists Robert St Amant and Thomas Horton wrote that:

tools can be thought of as mediating information flow between organisms.

To this they added the idea that tools could also help an animal or person to learn about their environment, without necessarily changing anything about that environment. Think of a telescope, or a temperature gauge, or in their example, a wild gorilla testing the depth of a body of water:

The notion of information flow could be another way to artificially separate humans out from the rest of the Animalia, simply because of the complexity of our language or our abstract thought patterns, but that is not inevitable. Provided we learn something of value from bringing information transfer into the definition of tool use, then this is an avenue worthy of further exploration.

Technically speaking

In their 2011 encyclopaedic review of animal tool behaviours, Robert Shumaker, Kristina Walkup and Benjamin Beck considered dozens of the kinds of scenarios we’ve run though here. Their aim was to update Beck’s own canonical definition of tool use from 1980, considering every type of behaviour and all the boundary-setting requirements above. Their solution isn’t elegant, but it is precise, and it represents the current state of the art in defining tool use:

The external employment of an unattached or manipulable attached environmental object to alter more efficiently the form, position, or condition of another object, another organism, or the user itself, when the user holds and directly manipulates the tool during or prior to use and is responsible for the proper and effective orientation of the tool.

All the ideas we’ve reviewed are in this definition. Objects (chopsticks, child, etc.) have to be external or outside the body. Using the tool has to change either the thing you’re interacting with, or yourself (updating knowledge about how deep the water is, for example), and you have to be manipulating it while it does the task.

Shumaker and his colleagues struggled with the exact phrasing, as they realised that ‘the act of definition consists in striving for consensus among experts, not elucidating an unambiguous categorical reality’. This fluidity around the margins is not unique to tools, of course; it’s found across most of the things that humans have tried to categorise, including such basic concepts as colour, or time, or life.

In the case of tool use we should see this fluidity as a feature. We need boundaries, certainly, or there is no topic to investigate. But too much restriction, as Johnson opined, might make things darker. And each time we exhort that such-and-such activity must be tool use, or can’t possibly be so, we join a conversation that has gone to the heart of what it means to be human.

Net-working

This has been a largely theoretical discussion so far. So let’s end with one of those potentially borderline cases, and consider the net-casting or ogre-faced spider (Deinopis sp). Here it is, net at the ready:

We know that tools have to be external to the body, which spider web is, once it’s been spun. They also have to be manipulated or controlled but the user, which most spider webs aren’t: once built, they’re static constructions. At the edge of this behaviour lies Deinopis.

Instead of the classic spider web form, with its radiating lines connected by a large spiral, Deinopis spiders first spin an open framework, and then a tight section (about 1 square cm) of sticky web. Holding this sticky section between their front legs, they cut the main line that connects it to the rest of the web, giving them mobility.

When a spider senses vibration and sees a flying insect behind it, they can instantly curl around to capture the prey. They spread the net as they do so, having spun it from spiral fibres that allow for this expansion, and they can use either side of the net to catch flying food. Alternatively, if they see an insect walking along a branch or leaf below them, they can pounce down and throw the net over it. Whatever they catch is then wrapped up neatly for consumption.

Every capture usually results in the web’s destruction, and it must then be rebuilt for the next strike. In this regard, the fact that the manufacturing centre for the spider’s tool is located inside its own body gives it an advantage that few other tool-users have. To some, this might even disqualify Deinopis net-casting from being tool-use altogether. What do you think?

Sources: Boswell, J. (1791) Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. London, Charles Dilly. || McLennan, M. et al. (2017) Gastrointestinal parasite infections and self-medication in wild chimpanzees surviving in degraded forest fragments within an agricultural landscape mosaic in Uganda. PLoS ONE 12: e0180431. || Hansell, M. & G. Ruxton (2008) Setting tool use within the context of animal construction behaviour. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 23: 73-78. || St Amant, R. & T. Horton (2008) Revisiting the definition of animal tool use. Animal Behaviour 75: 1199-1208. || Shumaker, R. et al. (2011) Animal Tool Behavior. Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press. || Breuer, T. et al. (2005) First Observation of Tool Use in Wild Gorillas. PLoS Biology 3: e380. || Coddington, J, & C. Sobrevila (1987) Web manipulation and two stereotyped attack behaviors in the ogre-faced spider Deinopis spinosus Marx (Araneae, Deinopidae) . Journal of Arachnology 15: 213-225.

Franklin image: Google Arts & Culture, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/benjamin-franklin-joseph-siffred-duplessis/ZgEyj5EEKdux-g || Archerfish image: National Geographic, https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2014/09/04/mystery-solved-how-archerfish-shoot-water-at-prey-with-stunning-precision || Gorilla image: Breuer et al. (2005) Figure 1 || Spider image: Carlos Guichard, Encyclopaedia of Life, https://eol.org/pages/1185961